Imtiaz Dharker is a Pakistan-born British poet, documentary filmmaker and artist. She won the Queen’s gold medal for her poetry last year and performed at Ledbury Poetry Festival this summer. The festival celebrates poetry in all its forms, and continues through to 12th July.

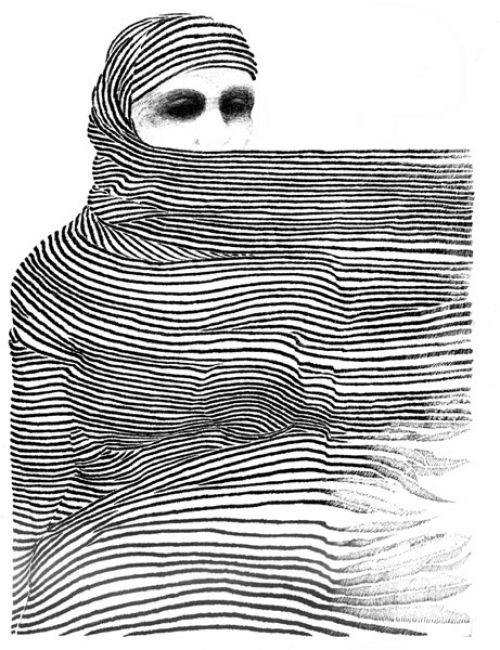

We spoke to Dharker about the festival and the themes of geography and home in her work. Our interview is illustrated with her drawings, more of which you can see on her website.

Do you prefer to perform your poetry aloud, or to see it written down?

When I write a poem I have to read it aloud to know if it works. That is the only way to check if the music is there, and if it sounds like a true voice. Reading the poem aloud makes it possible to detect the wrong note and find the rhythm. That’s just during the process of writing, but then there is the later stage of reading aloud to an audience and I enjoy that too. For me, one of the greatest pleasures is hearing a poet, perhaps half-understanding, then finding the book, reading, rereading and taking time to delve into the poetry.

At Ledbury, your work was included as part of an evening of poetry called 'Dangerous Women'. Would you say female voices in poetry are becoming more prevalent and valued?

I like the idea of being a dangerous woman. I think there are more spaces for all kinds of voices to be heard - voices that would have been suppressed or ignored earlier. Women are less inclined to censor themselves, less inhibited by who is listening and what they are thinking.

I love writing that explores the idea of the self and our relation to the spaces we inhabit. Your poetry is full of references to geography: India, Pakistan and Britain. One of my favourite lines in Purdah is, 'In the tin box of your memory, a coin of comfort rattles, against the strangeness of a foreign land.' What is the relation between identity, memory and space for you?

I love poems that have a location and a precise geography where places are named, even if the names sound mundane. I grew up reading literature and watching films that made the Underground stations of London or the streets of San Francisco as familiar as my own neighbourhood.

It feels good now to let the myths to flow the other way, to make readers walk the streets of Bombay or Lahore. In The Terrorist At My Table, the poems go in search of lost histories, the magic words and places, the idea of paradise, the dreams of people who have been reduced to one dimension and the mythology of cities that are remembered only as war zones.

You also explore the idea of home and what it means in your poetry, often alternating between spaces and countries, as in They’ll Say: She Must Be From A Different Country. Why does the idea of home fascinate you?

You also explore the idea of home and what it means in your poetry, often alternating between spaces and countries, as in They’ll Say: She Must Be From A Different Country. Why does the idea of home fascinate you?

Wherever we are born, wherever we live, our identity is always travelling, always fluid. I am changed every day by the things I see and the people I come across, or what I read or hear. So in Bombay (to me it will always be Bombay not Mumbai) the voices come straight off the street into my poems, and the soundtrack is rickshaw horns, rattling trains and lines from Arun Kolatkar.

In London, my background music is opera and my own footsteps on quiet streets and canals, because I am a walker and London is a great city to walk in. In Glasgow, my accent turns a little more Scottish and in the Vale of Clwyd in Wales, I feel related to Gerard Manley Hopkins. In the end, I feel most at home in the company of poets, alive or dead.