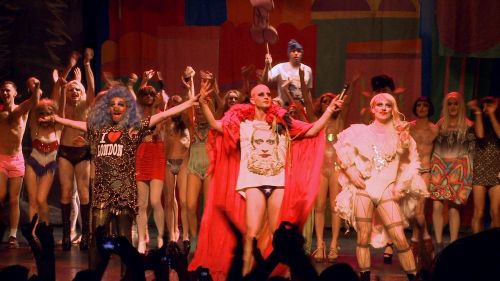

Nina Forever is constructed around a single elegant metaphor. Depressed supermarket employee Rob (Cian Barry), still mourning the death of his girlfriend, begins an uncertain relationship with his co-worker Holly (Abigail Hardingham), but whenever they try to have sex Nina (Fiona O'Shaughnessy) comes back to life to harangue the couple. The internal is made physical: Rob's grief assumes physical form, and it's that of the loved one he's lost, appearing naked, bloody and sardonic at the symbolic event of him attempting to moving on

With its ambitious visual language and sensitive depiction of bereavement, Nina Forever is the striking feature debut of Chris and Ben Blaine. We spoke to the brothers about lost loves and the benefits of close collaboration.

Bereavement is a sad, dramatic topic, but the film is also funny with horrific elements. Was it difficult to balance that tonally?

Chris Blaine: Not really. Partly it's a function of how we write, in a variety of different moods all at once, but I think it came out of our experience of grief. Often in films grief is the bit where you're sad and you look at the dead leaves and you go for a walk by yourself, and we both found that it was incredibly sad but also weirdly funny and terrifying. You have this strange embarrassment and almost magnetic sense of feeling everything all at once.

Ben Blaine: You also feel incredibly horny because you've lost someone and there's this big gap. So much of it is that presence of the person, their touch and their feel and their smell, so you've just got this desire and you kind of latch on to the next person that you see. I think Rob does that, where he's not jumping into this thing because he's thought about it, but because there's something deep within that craves the attention of someone else. He's lacking it from the person he really wants to still be there.

So many of Nina Forever's most crucial scenes take place during sex scenes that are using lots of practical effects. There's blood everywhere and the cast are all naked, and you're trying to tell an emotional story. How did you accomplish that?

BB: It was a challenge but one we knew we were getting into, and I think it was one of the things that excited us about making the film. We liked the idea of these scenes where the characters are totally honest and everything is absolutely stripped away both physically and emotionally. It was very difficult, that mixture of sex scenes with naked actors and the technical challenge of it all, but the emotions gave us something to steer us through. We could focus in on that, so we knew where our priorities were in the scenes. We knew that what really mattered was that the audience understands how these people are feeling, and as long as we were getting that we were on the right course.

As a film-making team how do you divide your labour? Do you do tasks together or do they naturally separate?

CB: In terms of writing we used to try to do individual passes of scripts, but we found that the best thing for us was to be in the same room and to talk about it constantly, and that's kind of how we do things all the way through to the edit. It's really liquid and it's not like there are assigned jobs. We slowly but surely we keep improving on each other's ideas because we're talking about the ideas rather than the words on the page.

BB: It's easy to fall in love with the way you've written something, and easy therefore to forget that no-one's going to see the script. The script is a blueprint and often not a particularly useful one, and so we find ways to talk about the ideas that we're actually going to put to the audience. Similarly that fluidity extends to the actors and the crew. It becomes a creative space for everybody who works with us, and anyone can come up with ideas.

That makes a lot of sense: the creative process starts as a conversation rather than the choices of a single person, and so it can easily expand.

CB: We really enjoy that. It's one of the things about film-making that's so great, the fact that you're working with loads of other people and it's not just you on your own. You've got a full cast and crew around you and crew who are all coming up with magical stuff and it makes the work and the experience so much better.

Nina Forever is available on DVD and Blu-ray from 22nd February. For a chance to win a copy courtesy of the Blaine Brothers, head over to our Facebook page and leave a comment on the post. The film will also screen at select cinemas throughout the month: https://www.ourscreen.com/film/nina-forever.

Images: Fetch Publicity