Painter Agnes Martin was an American artist whose work is known for its elegant colour washes and precise pencil grids. A rigorous editor of her own work, she destroyed many of the paintings she was not satisfied with. This summer, Tate Modern holds the first retrospective exhibition of Martin’s work since her death in 2004.

To the unfamiliar eye, the paintings can at first appear very similar. But each is a world of its own and, after visiting the show, I was keen to learn more about Martin's work. I spoke to Dr Lena Fritsch, Assistant Curator at Tate Modern, for her own perspective on the show.

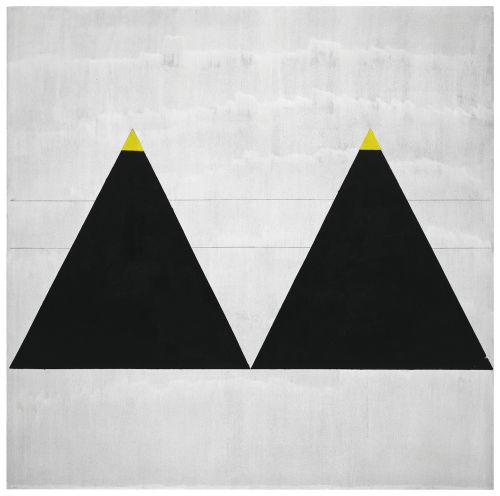

Agnes Martin, Untitled #1, 2003

Agnes Martin, Untitled #1, 2003

Tell us about your experience of curating the exhibition. I did my PhD in art history with a focus on Japanese photography so my expertise isn't Agnes Martin, but I think the way that I look at her work has changed a lot. At first sight and when working with reproductions, they all look the same. Martin said that too, actually. There’s a famous quotation from when she went to one of her own exhibitions and remarked that they all looked the same. But when you work on her paintings for such a long time, you notice all the variation and small details.

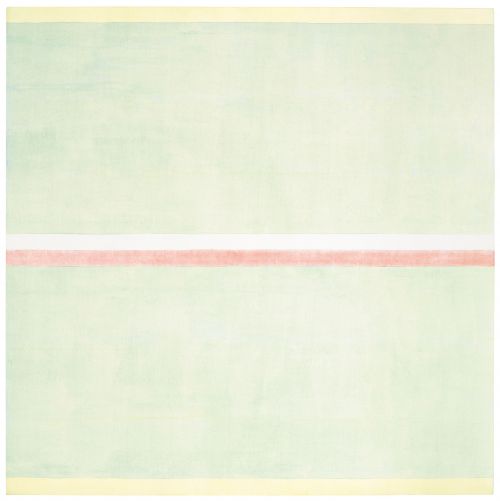

Agnes Martin, Gratitude, 2001

I saw a lot of the paintings online and I felt that they were all quite similar too, but seeing them in person is really quite different. Which part of curating the exhibition was the most interesting for you? What I’m really happy about is the work we received from private lenders, especially in room three, where we have the small, experimental works. People who know Martin’s work associate her either with the grid or her later striped paintings, but usually don’t think of an earlier sculpture like the Burning Tree (1961). Almost all the works in this third room are from nineteen different lenders!

There’s also a small painting, kept in a private collection, which was a wedding gift from Martin to the owners, and it has never been shown in a public exhibition before. It’s exciting to have such a personal work on show.

It’s only in the fifth room of the exhibition that we learn about Martin’s schizophrenia. Was that a conscious decision not to portray her as an artist with a mental illness from the start? Yes, in the fifth room it’s the first time that we mention it. We didn’t want to emphasise the connection too much, but at the same time we didn’t want it leave it out.

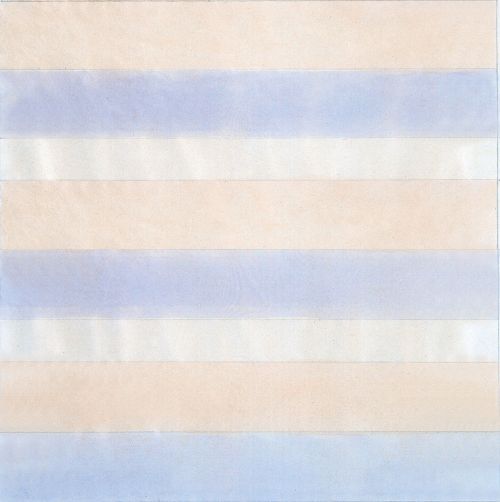

Agnes Martin, Untitled, Fondation Hubert Looser, 1977

You mention the way Martin sought solitude, most notably in 1967, when she took a five year break from painting and left New York for New Mexico. Do you think there’s a marked difference in her work afterwards in 1973? It’s interesting to see how the way she lived and the landscape in New Mexico influenced her work after the five year break. I’ve never been to New Mexico, but my colleagues went and said that if you look at the paintings, the light and landscape there makes you see them in a new way – the colours appear differently. In the grid structure, there are definitely references to her earlier work, yet in the colour there’s a strong influence from New Mexico.

Agnes Martin exhibition runs from 3 June to 11 October 2015 at Tate Modern. Admission £10.90 (£9.50 concession).

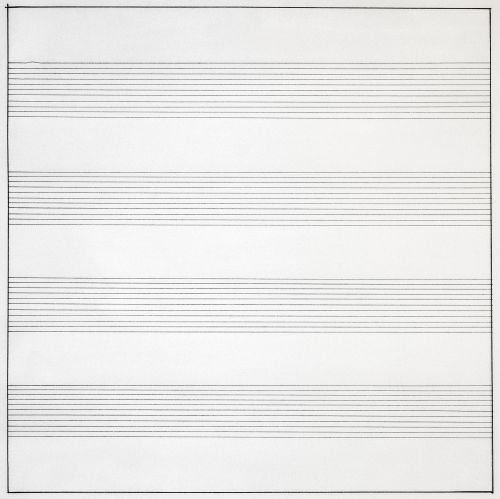

Agnes Martin, Untitled #10, 1990