In a brief pause on her whistle-stop book-signing tour, our book club editor Terri-Jane Dow caught up with author Samantha Harvey over a cup of tea in a bookshop basement to talk about Samantha’s new novel The Western Wind, covering story structures to how faith and secrets vie for power in the tiny 15th-century parish of Oakham.

Samantha Harvey, photo by Matt Lincoln

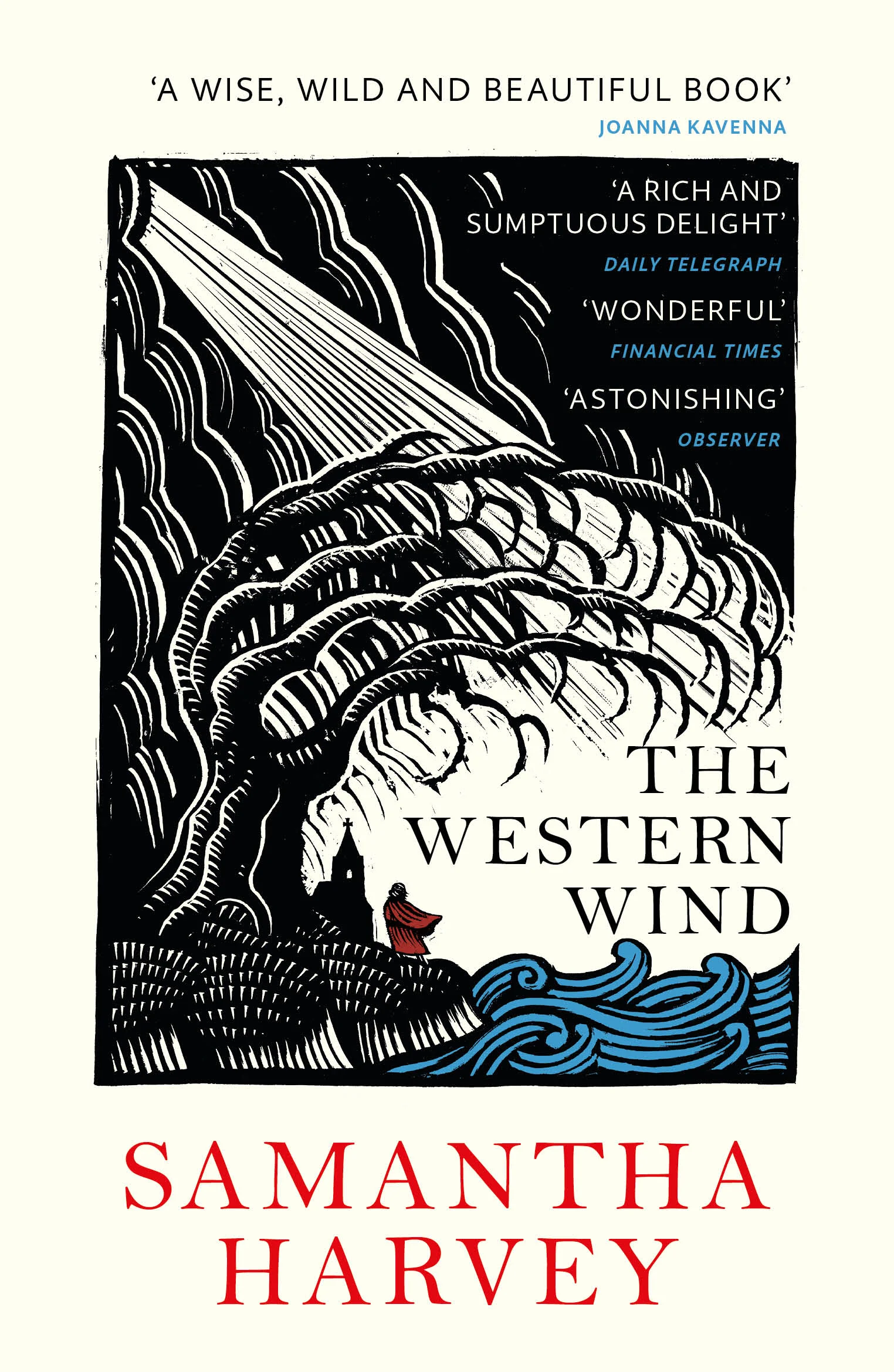

The Western Wind, a novel told backwards, looks at faith and power in a tiny 15th-century parish. Oakham’s wealthiest resident, Thomas Newman, is seen floating in the river on Shrove Tuesday, four days after his disappearance. A Lent visit from the Dean means that Oakham’s priest, John Reve, needs to find the murderer, when there perhaps isn’t one, and needs the Dean to leave before he finds anything more disturbing going on. Samantha Harvey’s latest novel is not a who-dunnit, but a why-dunnit and, by moving the focus from what could have been a straight detective novel, the result is something far more absorbing.

Terri-Jane: What drew you to write about this 15th-century village?

Samantha: What came before anything else was an abstract idea about wanting to write about confession. I went for a walk, and the concept, and the character of John Reve, the parish’s priest, came to me, and the idea of the story going backwards. Then I had to find a time and a place for it. I wanted it to be a time where confession was the social norm, and I ended up, really against my better judgement, in the late 15th century. I wanted the village to be somewhere that was on a potential trade and pilgrim route, but couldn’t exploit that because it didn’t have a bridge. So I looked at a map and invented Oakham. I could tell you exactly where on a map it is, but it’s not there.

T: The structure of the novel was so compelling. Why did you tell the story backwards?

S: I hadn’t meant to write a reverse narrative. I felt like it was a bit gimmicky, but it had come to me so solidly that when I tried to do it the other way, it wouldn’t work. I thought that I could take the readers expectations and subvert them, and make them less interested in the what and more in the why. As a reader, I’m not that interested in the gasps or the big reveal, but the workings of the human heart and mind are endlessly complex and endlessly renewing themselves.

T: There’s a sense Oakham is within reach of progress, but just can’t get to it. Reve supports the idea of a bridge, but he still wants to stay at the centre of the village, and he can’t have both.

S: Reve wants Oakham to modernise and thrive and flourish, but not if that threatens his position of power in any way. I wanted him to be a character who behaved as most of us would behave. Medieval priests would have this enormous power and trust from their parishioners, but also have immunities. You can’t go to Hell, you probably aren’t going to even go to Purgatory. Why would you ever want to lose that status? It’s your ultimate insurance against a sorry afterlife.

T: The book describes a ritual where Reve has to stand at one end of a boat and one of his parishioners at the other end, so that he can be weighed against a ‘regular man’. Even though it’s theatre to the extent that the other man has stones in his pockets, there’s a flicker of doubt in him that he’ll pass the test.

S: It must have been a peculiar thing. He will have known, as all priests of course know, that they are just like other men; they’re flesh and blood; they’re not halfway to the angels. At the same time they must really have believed that they were the mouthpiece for God. What a strange paradoxical position to always be in. The idea of the whole thing being a theatre that you have to play along with, but you also have to believe in it as if it weren’t theatre.

T: There’s a running theme through the book of the power that the church has in the village; before Thomas Newman’s death, he’s been away travelling and come back with some strange ideas, like that maybe he doesn’t need a priest.)

S: I wanted to look at that question of grief and loss, but also to look at divine power and how that was rationalised. That entirely Catholic society of the 15th century was very complete. If you would abide by it, the church gave you everything. It was your religion, it was the safety of your soul, or your body, of your afterlife. It was your insurance and your education. If your priest was trustworthy and cared for his parish, it was quite a complete system. But if you wanted to ask questions, or bypass your priest, it didn’t work so well.

T: The visiting Dean brings a much stricter version of that faith with him. He starts out as an unlikeable figure, but by the end, you realise that he just knows about some things that shouldn’t be going on.

S: I never saw the Dean as a nasty character, but I wanted him to come across like that in the beginning. His and Reve’s character arcs form a cross, and the Dean goes up in your estimations as Reve loses some grace. That’s the way we all are: complicated and flawed. Telling the story backwards meant I could tell the story from where they ended up, and then reveal things about them. I wanted to play with the effect that time has on a character. It was also quite fun, for the first time in my writing life, to write a villainous character. All of this is from Reve’s point of view, so of course his interest is in depicting the Dean as an adversary. And then we see that the Dean has more depth to him.

T: Reve justifies his actions as protecting Oakham, when really he’s just saving himself.

S: There’s the dual side of his character as man versus priest, but he’s also a self-centered individual and a person who has genuine compassion for his parish. Without a strong priest, a parish would be quite vulnerable. He’s caught between those two sides; for himself over a parish which is being corroded by a threat to his status. It’s not just his job; if he’s no longer needed as a priest, then does that mean he’s no longer safeguarded? Everything is at stake for him.

The Western Wind (Vintage) is out now