Anni Albers in her weaving studio at Black Mountain College, 1937.

Photo: Helen M. Post, Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina

Innovative textile artist Anni Albers is currently being celebrated at London’s Tate Modern. As a female student at the radical Bauhaus art school in Germany, Albers was discouraged from taking up certain classes. She enrolled in the weaving workshop and made textiles her key form of expression. The exhibition explores the artist’s creative process and her engagement with art, architecture and design and displays the range of her work, from small-scale ‘pictorial weavings’ to large wall-hangings and the textiles she designed for mass production. We spoke to curator Ann Coxon to discover more about this pioneering artist – and why her work remains so relevant to today.

This is Anni Albers’ first major UK exhibition. Why do you think it’s taken so long?

It’s because of the media. Because Anni Albers was first and foremost working with weaving. Because the art that she made was made with thread. She stopped weaving when she was older, because it was quite physically demanding, and started printmaking. Quite late in her life, she made some comments about how when you’re working on paper it’s considered art but when you thread it’s considered craft.

That legacy of dividing into art and craft has continued, even though the ethos of the Bauhaus – where Anni Albers studied – was to bring design, craft and art together. Even though that happened 100 years ago, I think we’re still just catching up! It’s really important that Tate Modern is showing that textile can be used as a fine art medium and putting it centre stage.

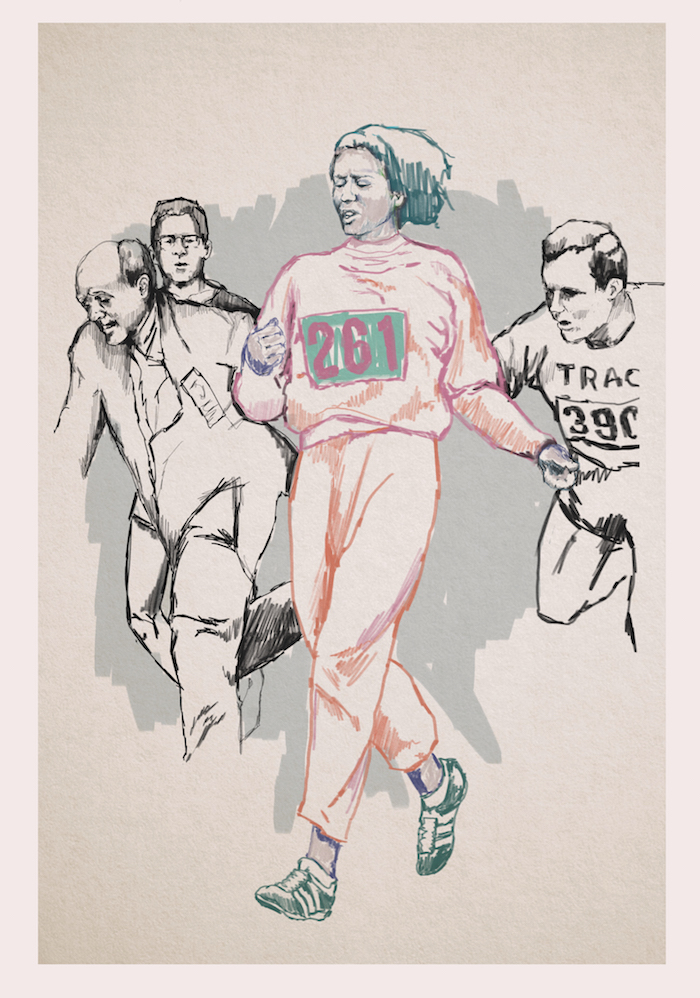

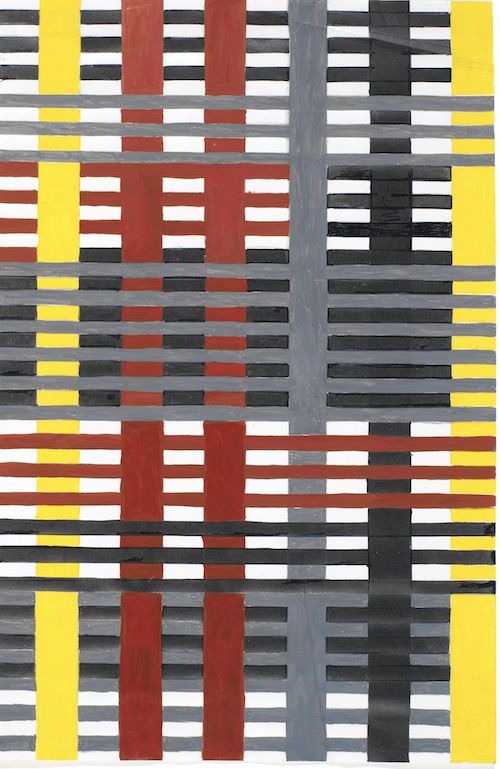

Black White Yellow 1926 / 1965, original 1926 (lost), re-woven by Gunta Stölzl in 1965, cotton and silk, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Everfast Fabrics Inc. and Edward C. Moore Jr. Gift, 1969 / Art resource / Scala, Florence © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Could you tell us a bit about the weaving workshop in the Bauhaus?

At the Bauhaus, students took a preliminary course, then chose a workshop. We don’t know exactly how it came about but we do know that the weaving workshop became known as the women’s workshop. That women both gravitated towards it and were encouraged to take it up and discouraged from certain other disciplines. For various reasons, weaving wasn’t her first choice, but she took it up and really fell in love with it when she found her creative outlet there. And so this incredible thing happened at the weaving workshop, when these women were exploring weaving as a form of modernist art making.

The Bauhaus disbanded in the mid-1930s with the rise of National Socialism and Anni, and her husband Josef, were lucky enough to be offered to be offered teaching posts at Black Mountain College in the United States. But some of her peers were not so lucky. Otti Berger, a contemporary of Albers at the Bauhaus, unfortunately died in Auschwitz. Anni was of Jewish heritage as well. In the 1960s, she got back in touch with Gunta Stölzl, who was head of the weaving workshop, or Gunta Stölzl reached out to her, and together they recreated some of the beautiful wall-hangings from the Bauhaus era that had been lost during the war.

Going around the show, you really get a sense of how naturally experimental Anni Albers was.

I think the interesting thing about weaving is that you’ve got this quite rigid format, with the vertical warp threads that are set up on the loom, then the weft threads get woven across and through and so you’ve got this grid framework really at the heart of the endeavour. What Anni Albers’ was interested in exploring is: what can I do with that? What are the variations? What happens if you twist the warp threads? What happens if you use this technique? Or this one? She was really thinking about how to push all the possibilities.

I’d previously seen her work as photographic reproductions and it’s amazing how different they look when you see them in person.

That’s something that really comes through in textile media. We tend to privilege the visual and the optic. What comes through with textile art is that there’s this tactile and haptic register: not just what’s seen but also felt. I think Anni Albers’ work really makes you think about the tactile. She was very vocal in saying – even at the time that she was writing in the 1960s – that we were starting to lose touch with what it means to make things with our hands and she gave the example of when you go out to buy your sliced bread, it’s very different to kneading the dough to make the loaf of bread.

Study for Unexecuted Wallhanging 1926 The Josef and Anniversary Albers Foundation © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

There’s something of a recent revival in weaving. Do you think it’s that desire to get back in touch with our hands?

Everything is very visual and the touchscreen fills our day. More and more, we’re all glued to our phones. Everything is communicated very visually and perhaps it’s that longing to get back to something a bit more tactile, literally a bit more homespun. Certainly, lots of a younger generation of artists seem to be making reference to Anni Albers’ work or beginning to use textiles again as part of a multimedia practice, such as Sarah Sze – whose work has recently come into the Tate’s collection.

The exhibition also emphasises Anni Albers’ wide range of cultural influences.

When Josef and Anni came to North Carolina in the 1930s, they travelled by road down to Mexico, and they both fell in love with Mexico and Mexican culture, history and making and they made several trips to different Latin American countries, such as Peru. Anni Albers referred to the Peruvians as her “great teachers”. She was very interested in pre-Columbian textiles, unpicking them to see how they were constructed and fascinated by the way that weaving was really the most ancient form of communication, of technology, of civilisation. To take that, to inspire her to make weaving a modern project. She’s really taking that ancient art form and making it modern.

Anni Albers, Six Prayers, 1966–1967. Cotton/linen, bast/silver, Lurex. 1861 x 2972 mm. The Jewish Museum, New York, Gift of the Albert A. List Family, JM © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

What would you say is Anni Albers’ masterpiece?

The very beautiful work, Six Prayers. It was commissioned by the Jewish Museum in New York as a memorial to the holocaust. It’s beautifully constructed. There’s a kind of light that shines out of it – it really is a masterpiece.

Anni Albers is at Tate Modern until 27 January 2019. Read about a stay at the Bauhaus here.