Photographer unknown, Rodchenko and Stepanova descending from the airplane. (for the film The General Line by Sergei Eisenstein), 1926. Courtesy Rodchenko and Stepanova Archives, Moscow

words: Victoria Rodrigues O’Donnell

With institutions like the Tate and National Gallery becoming more vocal about collecting and exhibiting works by women alongside projects like Katy Hessel’s The Great Women Artists Instagram account (featured in our current issue), the new exhibition at the Barbican, London, challenges our understanding of art history and women in Modernism. Showcasing the works of over 40 artist couples, ‘Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde’ seeks to reassess modern art and the influence of intimate collaborations on its development from the late 19th to mid-20th century. Little did I know that I would end up spending the next three hours walking through the space in enthrallment.

The modern couples in question vary from sexual orientation to location as well as artistic style and each room is dedicated to either a pair or group whose relationships inspired their creative output. It’s an understatement to call this an ambitious project, but I felt it succeeded most in shedding light on the works of women that have largely been overshadowed by their male partners and contemporaries. They even quote a reporter writing for the New York Evening Sun in 1917: "Some people think that women are the cause of Modernism, whatever that is."

+G+Walker,+Emilie+Flöge+in+Chinese+Imperial+costume+f13th+or+14th+September+1913,+1913.jpg)

Friedrich (Fritz) G Walker, Emilie Flöge in Chinese Imperial costume from the Qing Dynasty in the Gardens of the Villa Paulick in Seewalchen at Attersee 13 or 14 September 1913, 1913. IMAGNO Brandstätter Images, Vienna

Firmly established in the canon and soon to be celebrated in an exhibition at the Royal Academy, Gustav Klimt is joined here by his lifelong partner Emilie Flöge. While most of us are familiar with the legacies of Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, Flöge’s contributions to fashion design and success as an entrepreneur remain virtually unrecognised. In 1904, Flöge opened the couture house Schwestern Flöge with her two sisters where they would sell the latest in women’s fashions and accessories. Photographs of Schwestern Flöge on display show its changing rooms decked out with designs from the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop) – a style that would go on to influence Art Deco and Bauhaus. Flöge’s daring designs for modern women are perhaps best encapsulated by her free-flowing kaftan-esque smocks which rejected the rigidity of a corseted silhouette.

Sonia Delaunay, Stroll, 1923. Collection of V. Tsarenkov

Other women who worked with fashion and textiles as part of their oeuvre were Sonia Delaunay and Varvara Stepanova. The latter was a key figure in Constructivism, the Russian avant-garde movement better associated with her partner, Alexander Rodchenko, while the former is known for her colourful concentric paintings and patterns. Like Klimt and Flöge, these couples were advocates of art and design being integrated in all aspects of life. Although he dabbled with Neo-Impressionism, Robert Delaunay’s committed revolt against conventional painting methods and interest in colour theory would ultimately impact on his wife Sonia’s approach to designs for other mediums such as textiles, theatre and interiors.

In the wake of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Stepanova and Rodchenko were similarly dedicated to design that would be both decorative and functional. In the words of their collaborator and friend Vladimir Mayakovsky, “the streets shall be our brushes, the squares our palettes”. Not content with the limited reach of creating book covers, posters or photomontages, Stepanova moved her focus onto designing clothes for the everyday proletariat, concentrating on flexibility and dynamism – think bold colours, geometric shapes and chevron.

Queer love, particularly between women, is at the centre of a section entitled ‘Chloe Liked Olivia’. Referring to a line from Virginia Woolf’s seminal essay A Room of One’s Own, this ‘exhibition within the exhibition’ is devoted to the female artists and writers drawn to Paris’ Left Bank in the 1920s. The display features personal letters, photographs and publications capturing the intellectual and erotic exchanges between the women who moved within these circles. For over 60 years, Natalie Clifford-Barney, nicknamed ‘the Amazon’, ran a weekly literary salon frequented by the likes of Sylvia Beach, Gertrude Stein, and Djuna Barnes as well as Colette, Jean Cocteau and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Paintings by Romaine Brooks, her long-term partner, line the walls of the circular space and epitomise her distinct use of a monochrome palette.

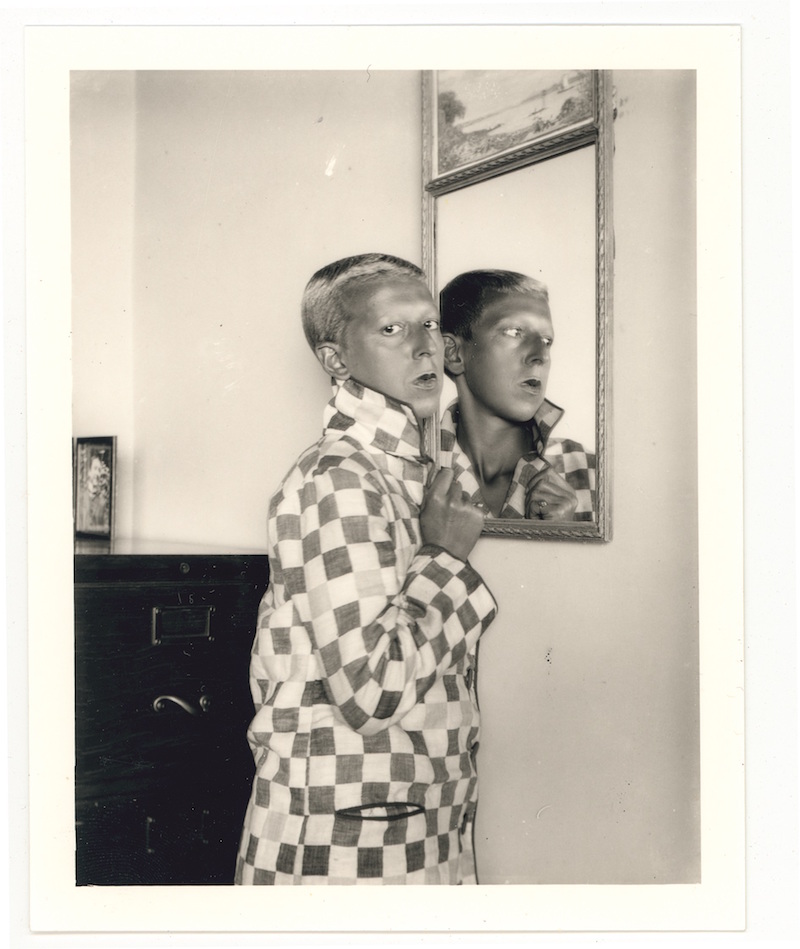

Claude Cahun, Self-portrait (reflected image in mirror, checked jacket), 1928. Courtesy of Jersey Heritage Collections

The significance of Woolf’s Orlando and its dedication to her lover Vita Sackville-West are also explored in the display. Inspired by this affair, Woolf wrote in her diary that the novel is “a biography beginning in the year 1500 and continuing to the present day, called Orlando. Vita; only with a change about from one sex to the other.” Moving fluidly throughout time and gender, Orlando continues to be just as transgressive as it was when first published 90 years ago.

Elements of the display reappear elsewhere in the exhibition, like the room dedicated to Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. Spanning across 40 years, Cahun and Moore’s relationship was already established when Cahun’s mother married Moore’s father in 1917. The two would go on to challenge gender stereotypes via experimental photography and collage throughout the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. The importance of mirrors, queer desire and subverting traditional notions around female vanity feature heavily in the couple’s work and are echoed in Cahun’s surrealist autobiography: “I am one, you are the other. Or the opposite. Our desires meet one another.”

From the tempestuous and obsessive to the intimate and tender, I was still contemplating all the ways in which art and love weave into one another during my tube ride home. ‘Modern Couples’ is a superb celebration of what can arise when these two coalesce; forging new paths into the unknown and shaping modern art as we know it.

Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde is at the Barbican until 27 January 2019.