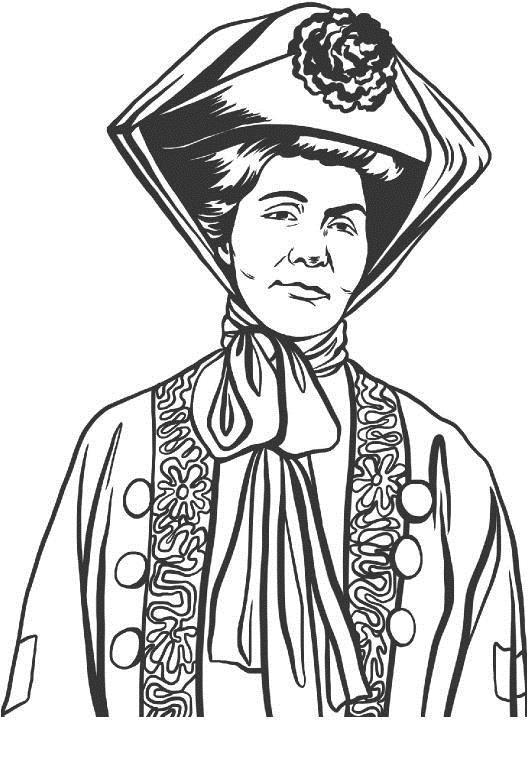

Illustration: Bijou Karman

Sometimes we all need a bit of guidance. Writers E. Foley and B. Coates have channelled the wisdom of remarkable women from throughout history for their new book, What Would Boudicca Do? From Hedy Lamarr to Rosalind Franklin, they show you how the examples of great ladies from the past can make your present a brighter place. Plus it’s illustrated by Bijou Karman (whose work also adorns our cover this issue). Here’s what we can learn from Emmeline Pankhurst about Getting Stuck In.

We live in deeply unsettling times. When ridiculous men with access to armies and red buttons seem to be in charge all over the place, it feels very tempting to put your fingers in your ears and shout ‘La la la la la’ to drown out the terrible noise our politicians are making left, right and centre. Tempting, yes, but wrong.

Emmeline Pankhurst, champion for the right of women to have a vote in the first place, would have stern (but motivational) words with you.

Born in Moss Side, Manchester, Emmeline Goulden was weaned on the intoxicating milk of radicalism, raised in a family burning with political passion. The eldest of ten children, she is said to have attended her first women’s rally at the age of eight, and her forward-thinking parents sent her to a Parisian finishing school in which she was instructed in the arts of book-keeping and chemistry, as well as the usual embroidery and etiquette. In 1879 she married Richard Pankhurst, a barrister 24 years older than her and buddy of the great reformer John Stuart Mill. With her husband’s support, Ms P. founded the Women’s Franchise League – one of their wins was ensuring that married women were able to have a say in local (but not general) elections. This was an early step in the struggle for votes for women – before this, you were lucky if you got a chance to pick the captain of the local knitting club – but still, only those women clever enough to ensnare a husband got their minute at the ballot box.

After Richard’s death at the age of 64, Emmeline managed, through the fug of grief, to find solace again in intense social campaigning. She founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1903 with her three daughters, Christabel, Sylvia and Adela. The Pankhurst gang’s goal was simple: votes for women in every election in which men could vote. Frustrated with a lack of progress on this issue across the party spectrum, Emmeline, with her gals at her side, set the political barometer to stormy. Their slogan was ‘Deeds, not words’, and boy, did they mean it.

The WSPU’s dramatic feats included arson attacks, pouring acid into mailboxes, and even (for the Fifty Shades of Grey fans among you) attacking Winston Churchill at Bristol Temple Meads rail station with a riding crop. One woman even took her meat cleaver to Velázquez’s Venus in the National Gallery; she said afterwards that she attacked the most beautiful woman in history as revenge for the government attacking the woman with the most beautiful soul in history – our very own Emmeline. Another, Emily Wilding Davison, ran onto the course at the Epsom Derby in June 1913 and was killed by the King’s horse. It’s worth noting that these high-stakes stunts were too much for some, and Sylvia and Adela abandoned the WSPU in protest, causing a family rift that never really healed.

When war broke out in 1914, the pragmatic Emmeline called a truce. She recognised that there was a greater cause to fight for – and that there was no point chasing the vote if ultimately there might not be a country in which to cast it. She switched her focus to campaigning for women to join the war effort, and as the boys went to the front to fight for Blighty, women began to take on more traditionally male occupations. Suddenly there were female tram drivers, farmhands and firefighters, and the ladies also took on roles in the civil service, police force and factories. It’s no surprise that women began to question why they were being paid less than their male counterparts for identical roles (and it’s frankly bonkers, not to mention really boring, that we are having to ask the same question over a hundred years later). Women’s rights were back in the spotlight and, in 1918, the Representation of the People Act extended the vote to women over thirty with some stipulations: they had to own property; or be married to a property owner; or be a graduate voting in a university constituency. So not much cop for our younger working-class sisters.

Emmeline died in 1928, agonisingly just two weeks before women finally won the vote on the same terms as their menfolk. Some hair-splitting historians have questioned whether it was Ms Pankhurst’s actions or merely the seismic changes of the war that meant that women were finally judged capable of having the vote without frittering it away on fancies. Was it simply that, with so many men dead, it was now impossible for the government to overlook women? In our eyes, Emmeline still deserves our respect, and more importantly we owe it to her to turn up and take part in our democracy – her activism paved the way for a future in which women’s equality has never been off the agenda. Yes, politics today is unpredictable and sometimes depressing, but women have a special duty to exercise a right that was so recently fought for and ferociously hard-won. In fact, we’d go so far as suggesting that the next time you have to vote – in a general election, for a staff rep or for the oddest-shaped vegetable at the village show – you make sure you put your best feminist fashion foot forward and array yourself in the WSPU colours of purple, white and green.

![What Would Boudicca Do[1] copy.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f2a4b54c2f85b03add7b89/1536329257855-4H6TRV8ER47C6IOHPD9Z/ke17ZwdGBToddI8pDm48kCEIcx2KCUlR2m_nF4CXrZMUqsxRUqqbr1mOJYKfIPR7LoDQ9mXPOjoJoqy81S2I8GRo6ASst2s6pLvNAu_PZdLwKcoejbCN47i7rcU72toYb-sX6Svyhd4RSnPqgFQViQQlep3ujLCu5LllTOiEN-E/What+Would+Boudicca+Do[1]+copy.jpg)

Taken from WHAT WOULD BOUDICCA DO?: Everyday Problems Solved by History's Most Remarkable Women by E. Foley and B. Coates and illustrated by Bijou Karman, published by Faber & Faber