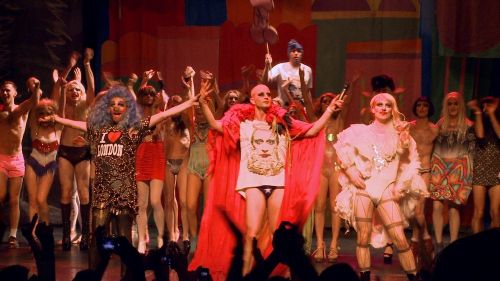

Photo: Irene Baqué

In issue 33 we say a sad farewell to the wonderful Linnea Enstrom, who has left Oh Comely to start a creative writing course in Sweden. We're delighted to introduce you to Marta Bausells, who will be taking on the role of music editor. To get to know her a bit better, we sat her down for a little chat...

Hello Marta! Tell us a bit about yourself and your work.

I'm a freelance writer, editor and curator. I was born and raised in Barcelona. I started out by writing about music and culture at the same time as I studied politics. At the time, I thought they were two separate things and that I'd have to choose, but I later realised that culture is intrinsically linked to society, politics and social action. I then worked for a newspaper there, where I was lucky to report on all sorts of topics – social issues, environment, foreign news – before I moved to London four years ago.

I love that my work has allowed me to learn and explore all sorts of subjects and ideas. I always wanted to go back to writing about culture, though, and I eventually landed a job on the Guardian’s books desk, where I hosted discussions about books, created a series about books set in American cities, chatted to book-lovers around the world daily, and discovered the wonders of the literary internet. Currently, I’m really enjoying working with Literary Hub on covering books from this side of the Atlantic.

I also do lots of other little things, like a collaboration with Subway Book Review (check it out!), which means I stop book-carrying strangers on the tube and chat to them about what they’re reading! It’s magical. No matter the subject, what I love the most about my job is that I get to meet fascinating people and share their stories. I can't wait to go back to writing about music!

What was the first single you bought?

The Spice Girls' 'Wannabe'!* It caught me at the exact target age, and everyone at my school was crazy about them for a year.

*If by bought you mean copied on a cassette tape and passed on among friends countless times (oops). But I'm sure I ended up buying it too!

What was the last gig you went to?

Well, this is a bit random – but it’s the truth! It was this Catalan guy called Ferran Palau. I had gone back to Barcelona for a few days, it was the end of the summer and it was starting to drizzle (that sticky, humid end-of-summer Mediterranean rain). One neighbourhood was celebrating its yearly festivities, which means the streets are beautifully decorated by neighbours and there are gigs in almost every little square. I had just discovered this guy’s music a few hours earlier in the car, with friends – and there he was. One of those serendipitous musical moments.

What song will always get you up and dancing?

Anything by Queen. I have a special weakness for 'Don’t Stop Me Now'.

Vinyl, CD or download?

The day I actually have space in the house and money to buy many of them, I’ll go back to vinyls – which is how I grew up listening to music. In the meantime, I’m a Spotify and downloads gal.

Who, dead or alive, would you most like to interview?

Frida Kahlo. I visited her house last year in Mexico and I was like “can I just move in here now?”. I would love to have been around her energy when she was alive, even if for five minutes. I am so inspired by how, despite being in horrific and crippling pain, she got up every morning, kicked ass and made the most amazing art – and lived her life in her own terms.

And if I might cheat and add a couple from the realm of the alive, right now my musical dream interviewee would be Solange – what a queen! I’d love to interview Michelle Obama once she leaves the Oval Office and gets to talk more freely. And Tom Hanks, always.

Outside of music, what else do you like to do?

Like I said, I love reading. My bedroom is ridiculously full of 'to-be-read piles' – it’s almost like I live around these book towers, and not the other way around. I also love film – I ran a film club with a friend for a while – good television and storytelling podcasts. I used to feel stressed-out or guilty about how little time there is to follow everything, but now I don’t mind being behind on TV shows or anything else. There’s this growing backlog of great culture waiting for me when I get home! What’s not to love?

Let us know a secret...

I don’t like chocolate… (!)

Find out more about Marta on her website, or follow her on Twitter.